First, a terminology lesson: “ Fairtrade” (one word) refers to Fairtrade International (FLO) / Fairtrade America. “Fair Trade” (two words) and “Fair Trade Certified” refer to Fair Trade USA (FT USA). “Fair trade” or “fair trade” refers to general fair-trade bodies and practices, but not a specific organization.

Until recently the two programs shared very similar rules about certification and the same pricing structure. However, on August 1st, the two organizations diverged in their minimum pricing levels. In a nutshell, FT USA will still acknowledge FLO contracts, but FLO will not acknowledge FT USA contracts. Read on for more details and impacts.

What does this news mean for our North American roasters?

*Any of our clients can purchase Fair Trade/Fairtrade coffee on our offer list. However, only licensees can use the “Fair Trade Certified" and/or "Fairtrade” label and use the seal/mark/logo on packaging and marketing materials. If you are not a licensee and do not use the label or seal, none of the following impacts you. If you ARE a licensee of one or both of these programs, read on.

*Atlas will start updating its naming convention on its coffees: any coffee listed as “Fair Trade” means that it was purchased prior to August 1, 2023, and can be sold as FT USA or FLO.

*Any coffee listed as (FTUSA) means it was contracted on or after August 1, 2023, under FT USA pricing terms and can only be sold into FT USA supply chains / use the FT USA seal. If you are certified with Fairtrade America, you cannot use the FLO seal or label the coffee as Fairtrade.

*Any coffee listed as (FLO) means it was contracted on or after August 1, 2023, under FLO pricing terms. Both FT America and FT USA-certified roasters can buy this coffee and use their respective seals. Dual-certified roasters can decide which seal to use and which supply chain to market under.

*For roasters with direct relationships with fair trade producer groups, we will work with both roasters and suppliers on the certification that works best.

*You are not alone! We are all feeling our way forward to meet the requirements of both systems, and we’re here to help you navigate. Please reach out to your rep with any questions.

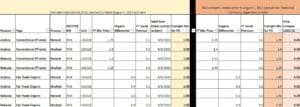

Table 1: Fairtrade minimum pricing changes

For more background on FLO and FTUSA, read on:

Origins

The history of fair trade coffee is long and complex. The first Fairtrade coffee was imported from Mexico into the Netherlands in 1989. Throughout the 1990s, numerous national fair trade networks sprouted up, and in 1997, 17 of these Fair Trade organizations officially joined forces to form an umbrella organization called the Fair Trade Labeling Organisations International (FLO International; also known as Fairtrade International, or FLO for short).

Fair Trade USA leaves FLO

Fair Trade USA (FT USA) was formed in 1998 and was FLO’s affiliate organization in the United States until 2011, when FT USA split from FLO over diverging philosophies on several topics, including who should qualify to become Fair Trade certified. Until 2011, only smallholders grouped into cooperatives qualified to become Fairtrade certified, but FT USA went for “a higher-volume approach, in particular extending its remit from helping smallholders grouped in cooperatives to working with large farms and plantations.”[1] This applied to not only coffee but all its Fair Trade Certified products.

Fair Trade America Formed

In 2013, FLO launched Fairtrade America (FT America) as its new US affiliate. US Roasters now had a choice: become/stay certified with FTUSA, become certified with FT America, or become dually certified (in the cases where they sold into non-US markets that preferred the FLO seal). While most roasters in the US are certified through FT USA (due in part to its establishment 15 years prior to the creation of Fairtrade America), most producers are certified by FLO.

Fair Trade USA Producer Recognition Program Begins

To find a workaround solution to this challenge, FT USA launched a Producer Recognition Program so that producer organizations who are certified by FLO can submit their FLOCERT2 certificate to Fair Trade USA free of charge and be able to sell into FT USA supply chains. This allowed FLO-certified producer organizations to sell into FT USA supply chains while avoiding the inconvenience and cost of obtaining a second certification through FT USA. Conversely, it allowed FT USA-certified buyers to buy from FLO-certified supply chains and sell using the FT USA seal.

Fairtrade is Fair Trade

In this sense, for all intents and purposes, FT USA-certified buyers could buy coffee from FLO supply chains and sell it as FT USA coffee and use the FT USA seal, just as if they had purchased coffee from an FT USA supply chain.

By and large, this system worked: both certifications have similar missions, with FLO’s being “to connect disadvantaged producers and consumers, promote fairer trading conditions and empower producers to combat poverty, strengthen their position and take more control over their lives”[2] whereas FT USA’s is to build “an innovative model of responsible business, conscious consumerism, and shared value to eliminate poverty and enable sustainable development for farmers, workers, their families, and their communities around the world.”[3] And, notably, both groups had the same minimum pricing models.

Fair Trade is not Fairtrade: Different Minimum Pricing Models

Then came the great pricing rift of 2023: On March 30th, 2023, FLO announced an “increase in its baseline price by 19 percent and 29 percent for Fairtrade certified Robusta and Arabica coffee, respectively,” citing “inflation, skyrocketing production costs, and crop loss due to the effects of climate change,”[4] among other reasons. Beyco published an interesting blog article with more background details about the price increase.

Then, on July 6th, FT USA announced that based on interviews with stakeholders and fear that the pricing increase would ultimately harm producers, it is keeping the “old” minimum pricing benchmarks.

Confusion ensued for many producers, traders, and roasters about the ins and outs of the changes, and about how to manage contracts, reporting, labeling, and pricing. The most common phrase I’ve heard in multiple meetings and webinars on the divergence and implications is primarily “wait and see,” but FT USA did publish a FAQ document to address some concerns. FLO similarly published a downloadable pdf Q&A here.

Bukonzo Joint Cooperative Union's Nyabisusi micro-washing station.

A Time of Uncertainty

Both producers and roasters are faced with many questions and feeling a fair bit of uncertainty. A producer organization whose main market is the US will undoubtedly face more pressure to sell under FT USA terms than a producer organization who has other markets outside of the US (remember, it’s only FT USA that is keeping the lower pricing model; if a producer sells anywhere else, the higher FLO minimum price applies).

There’s also some fear and speculation among roasters about availability and quality issues – if a producer organization can receive a higher price under FLO but feels pressure to sell to a US buyer under FT USA pricing terms, there is a concern they may deprioritize the FT USA sale’s shipment or quality.

Today, a high percentage of coffee purchased from FT USA/FLO-certified producer organizations is still sold as conventional – and FT USA worries that that trend will only increase, incentivizing producers to leave Fairtrade/Fair Trade altogether and potentially consider another certification scheme or sustainability model.

On the other hand, the volume of Fairtrade coffee sales doubled between 2011 and 2022 to 3.8 million bags[5], and the Fairtrade and FT USA labels increasingly resonate with and are recognized by consumers. Inflation is also a huge issue, compounding the poverty and living-income challenges many smallholder farmers already face, and FLO's higher prices are meant to address this inequity.

It also appears that the number of coffee producers becoming Fairtrade (or FT USA) certified is outpacing the demand for Fairtrade/FT USA coffees or that some producers who are certified Fairtrade/FT USA haven’t found the market demand they predicted.

Undoubtedly this mismatch is due to several factors. For example, the fair trade certification process takes on average much less time than the organic conversion process, so many producer organizations begin with becoming fair trade certified while concurrently or subsequently starting the three-year organic conversion process to become certified organic.

Additionally, many grants that producer groups apply for include certification scheme set-up/costing, regardless of the market demand for their coffee being Fairtrade/Fair Trade.

Conclusion

There is so much data to pull from; each side can provide a well-researched and data-driven case for why their pricing model better matches their mission.

The industry clearly and often states the sentiment that producers are the most vulnerable links in the entire coffee supply chain while simultaneously being the most necessary. “No farmers, no coffee”, as the saying goes. If we do not respond to the increasing cost of production, producers lose. If the consumer market won’t bear the cost increases and demand diminishes, producers lose.

In light of the options offered by the Fairtrade/Fair Trade certification scheme, traders, roasters, and producers will need to, conversation by conversation, find a way toward an equitable pricing model that fulfills the mission of what it means to produce, buy, and sell fair trade coffee.